I recently reconnected with a college friend who is a cinematographer that has worked around the world. Greg is renowned for his ability to capture television footage while suspended on a rope with 80 pounds of gear and more than 20,000 feet of thin air below him. Running into him reminded me of my first alpine climb and this photograph.

I first met Greg back in 1989 when we were both studying photography at Spokane Falls Community College. He was into competitive cycling and had already begun his television career riding pillion seated backwards on a motorcycles while filming bike races around the world.

One day when I hobbled into the studio on crutches he asked me what I had done. I told him that I had fallen while rock climbing in preparation for my first mountain climb. I had fallen in love with backpacking during my first spring break of college when a friend and I had spent a few days hiking in the Hoh rain forest. I wanted to take my adventure to the next level. A friend of my fathers told me about the mountain climbing school put on each spring by the Spokane Mountaineers. He even loaned me an ice axe and a pair of 12 point crampons.

Since I was a broke college student I hobbled together the rest of my kit necessary for climbing in the cold. I purchased a rubberized parka with a hood and a pair of Belgian Military wool knickers from a surplus store along with long underwear and a wool sweater and hat. I had some old Norwegian welt stitched leather boots that I took to a shoe repair shop where I had them resoled with a full steel shank installed so I could climb ice.

I bought an internal frame backpack, -20 degree sleeping bag, cook stove, and rope from Mountain Gear’s original shop down on Sprague. I got a used copy of the Freedom of the Hills mountaineering textbook and I would frequent used bookstores to buy every mountain climbing book I could find.

I was absolutely hooked on the idea of climbing. I remember reading the book Four Against Everest by Woodward Wilson Sayre about he and three other friends who attempted to be the first to climb the highest peak in the world fully self supported with nothing more than what they could pack on their backs. They were pioneers of the light and fast expedition style that is more common today.

I was not a very talented climber. Even at my best a few years later, my climbing partner David would made fun of my lack of nimbleness on the rocks where my three points of contact always seem to look like it included my head!

The week before my mountaineering class was scheduled to head up to Canada for our graduation climb my classmates and I were working on some bouldering moves at Minnehaha rocks when I managed to fall from about 10 feet off the ground and roll my ankle.

I was crushed because it seemed like I would not be able to finish the class and my dreams would have to wait an entire year for the next opportunity to graduate from the class.

Greg listened to my story and offered to loan me his pair of Koflach heavy duty climbing boots. He explained that they were made of plastic and extremely stiff which might give my ankle the support it needed to push on if I had healed enough in the five remaining days before the climb.

Each day after school and work I would elevate and ice the ankle and hope for a quick recovery. The climbing instructors offered up that I could come along on the trip and hang out at base camp even if I couldn’t climb. I was only 19 at the time and one of the youngest students in the class. Most of the people taking the class were in their 40s and were empty nesters looking to do something they wish they had done sooner in life. There were only two other students close to my age. Anthony and Doug hitched a ride with me in my 1975 pale blue K-5 blazer with removable top with a 307 Chevy V8.

We were full of excitement and bravado as we sped along the highway eagerly passing as many cars as we could and listening to loud hair band rock music for the nine hour drive up to the Columbia Icefields just beyond Banff.

As we neared Banff, we took a side trip along the Bow Valley parkway. We stopped to look at some mountain goats and a rocky outcrop. Anthony was a wild child who ignored our warnings and started climbing unprotected up the rock to a ledge where a furry white goat stared down at him from. In my mind I could feel the fall and ankle sprain from climbing without rope the week before and I worried for Anthony. He was an absolute natural at climbing and scurried up the rock with as much ease as the sheep above that had stopped and crooked his neck to watch. Anthony got within a couple of feet of the goat and the two had a brief and meaningful exchange in silence. I have come across goats many times since then and I am always impressed with how peaceful and quiet they are. It’s like they have a wisdom and are indeed the guru at the top of the mountain.

Anthony skillfully climbed back down and we resumed our drive to the meeting spot. At basecamp I was still limping a bit and worried about whether I could make the climb the next day. That night our lead instructor came around with the rope assignments. Bill told me that the three of us were assigned to his rope and that we would be the first team to head up starting at 2 am while the ice on the glacier was solid and the risk of a crevasse opening up and us falling in would be less than after the sun came up and warmed the snow.

Bill asked me if I thought I could make the climb and I said I wanted to try. He would put me in the last position on the rope in case I ran into trouble and needed to stop somewhere safe along the way and wait for their return.

There was a lot of excited banter at base camp the night before the climb. We had come from the lowlands of spring where the air was warm and the land was filled with green grasses and were now at an ice field at the terminal moraine of a glacier. It was a winter scene of snow, rock, and ice and my jittery tummy confirmed that I was indeed on a real adventure.

I had a restless sleep which made it easy to be awake and out of the tent by 1am. It was quiet and you could hear high pitch hiss of gas cook stoves heating water to a boil against the low rumble of subdued conversations. Camp looked like a constellation of moving stars from each person’s headlamp. Once I had my stove on and the water pot on the burner I turned mine off to look up into the dark sky. You could just make out the outline of the mountain.

Twenty minutes before departure I assembled the last of my 10 essentials into my pack and put on the plastic climbing boots. I kept hearing one of the other instructors from class voice in my head lamenting the frustration he felt when climbing team members are late to the start of the climb. He called it the fiddle factor when climbers pack, repack, and fuss with gear and are late to the start of the pitch. I was 10 minutes early and nervously walking around testing out my ankle. While it still was tender, I felt surprisingly good. The stiffness seem to keep my ankle planted in place so it didn’t roll or flex side to side which cause the sharp pains. Five minutes before two Bill came around to us and said time to go.

Bill warned us to start out slow and steady as we navigated a trail through the rocks to get to the glacier. It was cold and he didn’t want us burning unnecessary energy that we would need to keep in reserve for later in the climb and he didn’t want us sweating which could become dangerous as the temperatures dropped the higher we climbed.

In the dark you just pay attention to the steps of the person in front of you. I especially did so because of my tender ankle. I didn’t want to trip or stumble and risk more injury. After a time we reach the spot where would would step off the rock on to the glacier. We would rope up and space out about 30 feet apart. We were on the A.A. Col route that follows the A.A. glacier up to the pass between Athabasca and Mt. Andromeda to the West Ridge, and then follows over the Silverhorn sub peak to the summit.

The climbing itself wasn’t as difficult as the rock climbing we had done in class. This was a classic alpine route as opposed to a multi-pitch technical rock climb. The real adventure was simply the need for heightened awareness of every one of the five senses to manage the risk factors of falling rock or avalanche. Situational awareness to maintain the correct spacing between you and the next climber to not allow too much slack and to be ready to drop to the ground and dig in the ice axe to create a safety anchor in case someone fell into a crevasse or slipped on the 40 to 50 degree slope. Vigilant monitoring of your mates and the landscape along with your own internal body temperature, hydration, and energy kept the mind occupied. It was only when we stopped for water breaks that you could really take a look around and appreciate the stars above and the stream of lights of the climbing teams below you.

We had been climbing steadily for 3 hours before the sun finally rose and we could see the grandeur around us. It was getting cold and time to add more layers and to have a snack. By the time we made it to the West Ridge at around 10,000 feet of altitude I thought I was going to throw up. For me, 10,000 feet was the beginning of the real alpine range that tested my body’s stamina. The air is thinner and the sky turns a deeper shade of blue. It is like sea sickness for sailors. I just needed to take some time to rest and get climatized. After a break we continued on to Silverhorn which was just about 11,000 feet.

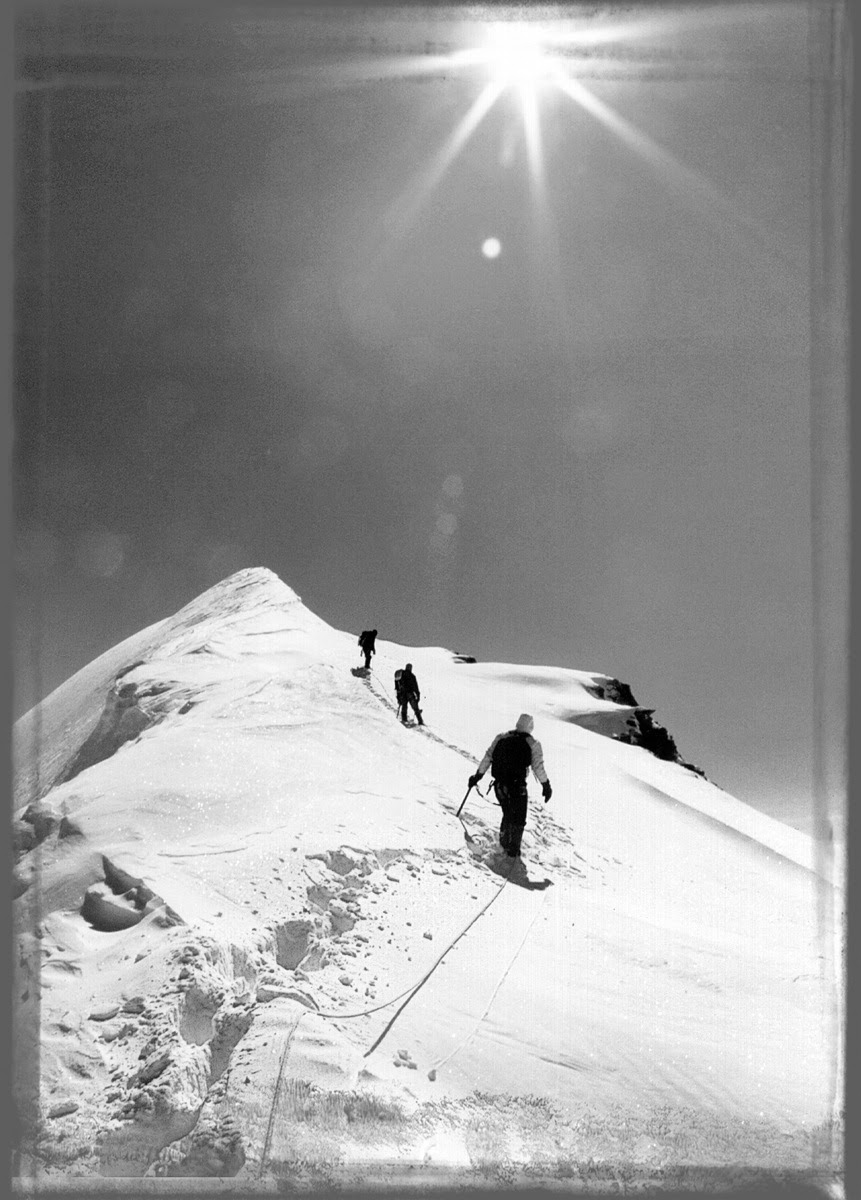

By the time we reached Silverhorn the sun was out and I knew I would achieve the summit. I was filled with excitement. I had lugged my father’s old Nikon F2 with and pulled it out to make a photo of our team as we approached the final summit. What is significant to me is that there are no footsteps beyond the front of the rope. We were all alone up there on fresh snow. Nobody else behind us would get to experience this and I wanted to make a record of that moment. We stood at the summit for just a brief moment. The wind picked up and I became accutely aware of just how cold it really was and how dangerous lingering here would be. We dropped back down off the summit to a shelf that was protected from the wind and sat on our packs and ate lunch. It was 10 am and we had been climbing for eight hours. In less than half an hour we would load up and start the descent.

With the daylight came the greater risk of loose rock and ice and we gingerly picked are way back down the mountain. By the time we reached base camp again it was 4pm. We had been climbing for 14 hours essentially non-stop. I had never worked so hard to achieve a goal than I had in this one day. The since of humility, gratitude and achievement combined to produce a wry grin that stayed with me for days afterwards.

That first summit was a life defining moment, and a memory I recall whenever I am faced with fear and fatigue. It is a reminder of the joy that comes from pushing through pain and struggle to achieve a goal and to receive the reward of nature’s wonder and awe.

I quite climbing when my son was born. I had experienced a couple of near death experiences in the mountains which did not deter me from wanting to keep climbing but fatherhood triggered a deeper emotional need to be fully present for my son.

Regardless, there have been many adventures since that first trip so long ago and I continue to seek out nature’s beauty as often as I can.

Kindest Regards,