First of all, let me be clear about one thing… I never met Ansel Adams. The closest I could claim to ever getting to meet Ansel Adams was spending time in Theo’s Pipe Shop and Used Cameras store in downtown Spokane once while I listened to Theo tell a story with his Greek accent about how Ansel Adams kicked him out of Yosemite once for being a bother to him while he was trying to work.

I suppose another vicarious close call would have to be the story my friend R.L. tells of how he and another friend Jay drove down to Ansel Adam’s house in Carmel in a camper van and met him once. But that turned out to be a dream sequence in R.L.’s imagination that Jay was quick to correct. For them going to his house was like a trip to Mecca.

I suppose I know Ansel Adams in the way that Julie Powell got to know Julia Childs by cooking every recipe in her book Joy of Cooking.

Like many photographers I was inspired by the work of Ansel Adams. I read every book he wrote about the Zone system and I read his autobiography. I collected every newsletter written by his printing assistant Fred Picker who went on to start the Zone VI camera company. I read those letters like I read E.B. White columns in the Harpers Monthly.

I even went on to develop and teach an advanced black and white film photography course based upon the Zone system. I studied every aspect of his technical mastery until I had a command of it. And then I walked away from it for much of the last 20 years. I chose a different path away from landscape photography and yet the influence of Ansel Adams has followed me everywhere I go.

I remember the first time I read about how he made the image of half dome and pre-visualized what it would look like if he added a red filter over the lens. For the next six months I put a red filter over my lens for every exposure. My images were terrible.

Finally one day while I was making an architecture image a gust of wind blew the filter off of my camera and into the busy street where a car ran over it. It was the best gift I could have received!

You see I had been emulating Ansel Adams without understanding. I was copying without any comprehension of how the technical and the aesthetic worked together.

I didn’t realize until later that the reason my photographs looked terrible was because I was in Spokane Washington photographing a landscape filled with evergreen trees that the red filter was turning almost black. My images were dark and muddy.

I hadn’t realized that the grey monolith that Ansel Adams had photographed was reflecting equal parts of red, green, and blue light which meant there was still plenty of texture and detail to be had in the granite rock while letting the blue sky go dark. I was just making dark green trees disappear in the daylight. A most unwanted magic trick!

I made my first trip to Canada with a 4×5 monorail camera and a goal of making landscape images of the Canadian Rockies. I made this photograph of Mt. Athabasca in 1989 using 4×5 Tri-X film during my second year in college.

I got out of classes on a Friday afternoon and drove all night up towards Banff Canada in my 1975 Chevy K5 Blazer. I eventually grew so tired that I pulled into a pullout along the highway near Castle Mountain and slept. The next morning I was awakened by a Canadian Mountie who was warning me that I had parked next to a Grizzly Bear trap!

As I get to thinking about how Ansel Adams has deeply influenced my work over the years I realize that it goes far beyond landscape photography. I never really matured into a landscape photographer and have spent most of my career as a portrait artist.

A student of mine was doing a research paper on Adam’s work and we had a conversation about which of his images were our favorites. I realized at that moment that the image that stood out to me the most is not one that I teach about very often. I tend to teach about his mural images and talk about his periods of moving the horizon line from the upper third to the lower third of the frame. I also talk about the juxtaposition of textures in the still life of a rose on driftwood.

When I teach about Ansel Adams I reflect on how he stayed true to his vision of the importance of photographing the primordial landscape even while facing criticism for seemingly ignoring the conflict of World War II.

He was criticized for photographing rocks and trees while the world was going to hell. It wasn’t true of course because he did pay attention to human suffering in his images of the Japanese internment camps.

Ultimately I think he was keeping our eyes focused on geologic time and the importance of nature. I think he understood that primordial beauty gives us hope and perspective enough to see the trivial nature of our greediness throughout our minuscule life span. I think that is the lesson that stands out most to me.

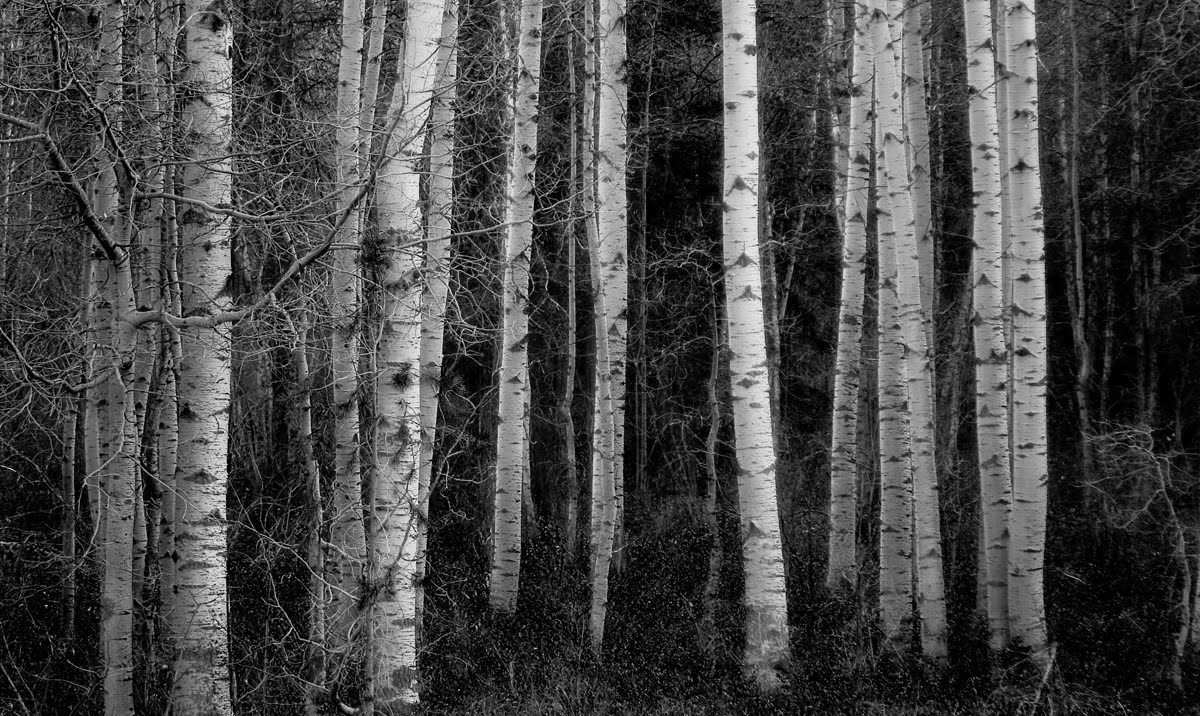

However, in the moment of discussion about which image resonates deepest to me it was a simple image of quaking aspen glowing against the rhythm of larger Apsen tree trunks set against dark shadows. It reminds me of looking at the black and white keys of a piano.

I never seriously pursued landscape photography as a profession and yet this one image has singularly influenced my whole approach to photography of any genre. The contrast and rhythm of the light values against darkness in that image is what I strive for in my best work.

Whether I am photographing a wine bottle or dancers in the studio, a figurine on top of a trophy, or tree trunks of birch and aspen, it is this chiaroscuro of deep tones contrasting with near specular highlights that arrests my eye and satisfies me like no other image can.

The beauty of light and dark, yin and yang, keeps me humble and enchanted.

Happy Friday,

Ira

Photos:

Top – Mt. Athabasca photographed in 1989 on 4×5 Tri-X Film

Middle – Castle Mountain photographed in 1989 on 4×5 Tri-X Film

Bottom – Aspen Trees photographed near Cranbrook Canada in 2008 on Canon EOS 10D digital camera with #47 blue filter.